Daily tide like breath

exhale, reveal salt secrets

Limpet on a rock

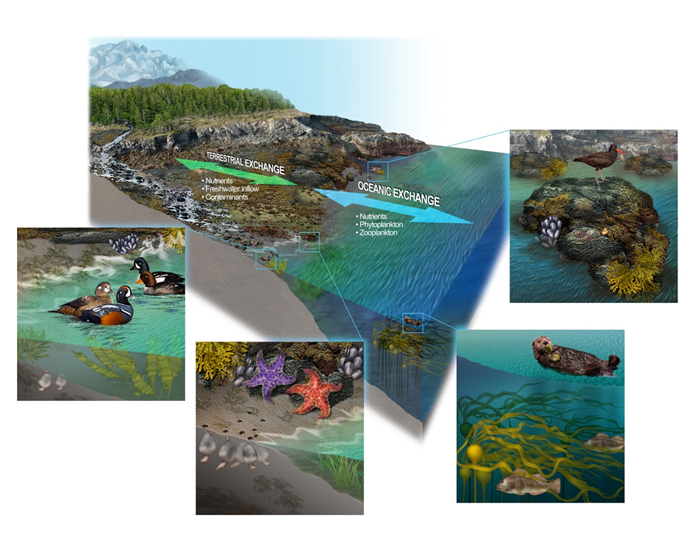

At the interface between oceans and continents lie nearshore ecosystems, defined by well-known species with well understood ecological relations, where high densities of specialist predators (sea otters, sea ducks, black oystercatchers, sea stars) exist within a diverse and productive system full of kelps and invertebrates that don’t occur in any other habitats. This is the marine ecosystem that is most familiar to and highly valued by society.

Conceptual illustration of the nearshore food web with terrestrial and oceanic influences indicated. Sea otters, black oystercatchers, sea ducks, and sea stars act as top-level consumers in a system where primary productivity originates mostly from the macroalgae and sea grass and moves through benthic invertebrates to the top-level consumers.

Why are we monitoring?

Nearshore marine ecosystems face significant challenges at global and regional scales, with threats arising from both the adjacent lands and oceans. Monitoring composition and abundance of species and understanding functional relations in the nearshore ecosystem is essential when responding to and managing present and future threats. The legacy of knowledge provided by prior nearshore science allows us to tease apart human threats from naturally induced causes and provide guidance for management of those valued resources.

Many species depend on nearshore habitats, including several with well-recognized ecological roles in the nearshore food web. Our work describes patterns of change in those species and identifies probable causes in order to support management and policy decisions for nearshore resources.

Our goal is to understand what drives change in Gulf of Alaska (GOA) nearshore ecosystems. We focus on key components of the nearshore food web, including primary producers, benthic invertebrates, and apex predators. The questions we are exploring include:

- What are the spatial and temporal scales over which change in nearshore ecosystems is observed?

- Are changes related to broad-scale environmental variation or local perturbations? What are the specific drivers?

- Does the magnitude and timing of changes in nearshore ecosystems correspond to those measured in pelagic ecosystems? Do some drivers affect nearshore and pelagic ecosystems differently?

Where are we monitoring?

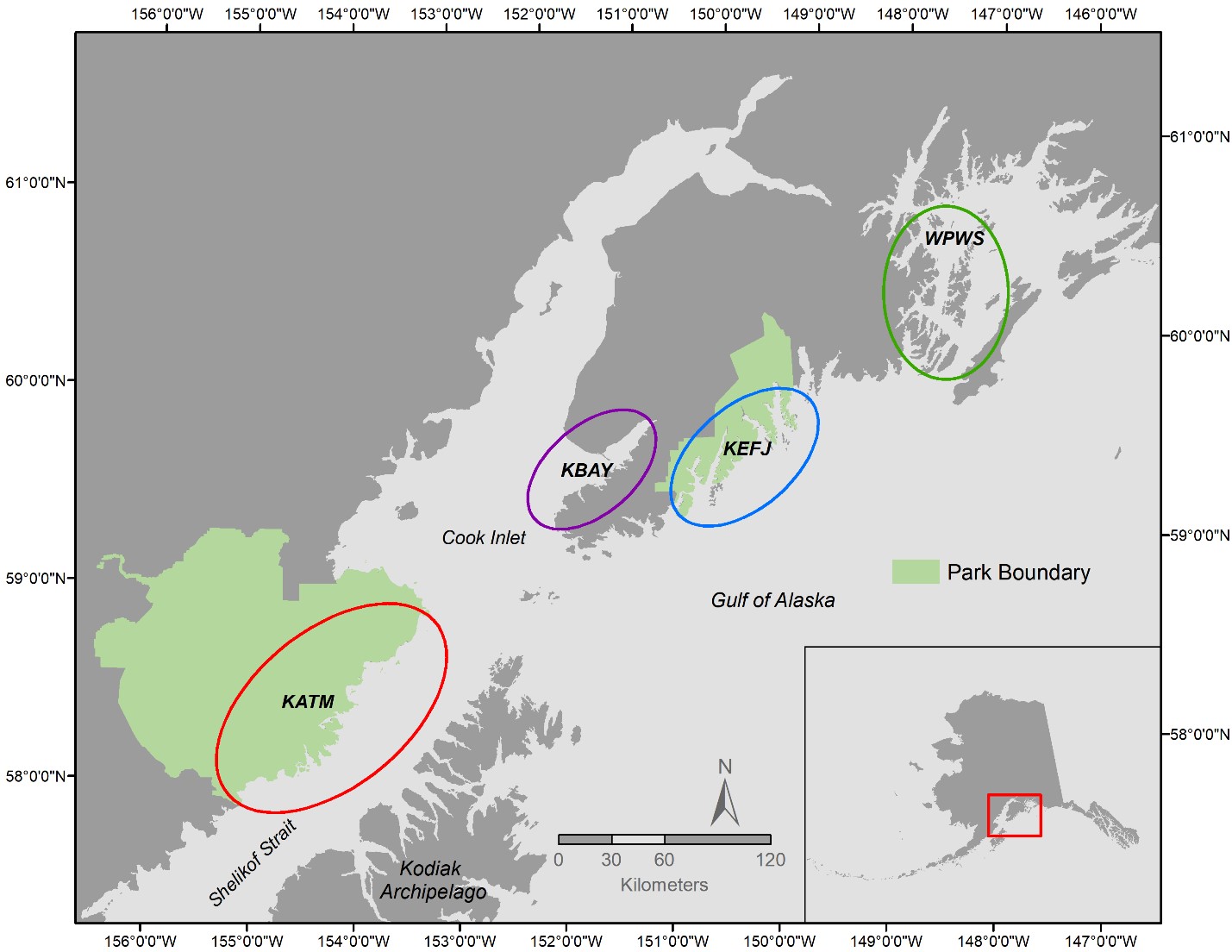

Through participation by many institutions (including National Park Service, U.S. Geological Survey, University of Alaska Fairbanks, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), we monitor nearshore ecosystems across a broad swath of the northern Gulf of Alaska within the area affected by the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Study regions include western Prince William Sound (WPWS), Kenai Fjords National Park (KEFJ), Kachemak Bay (KBAY), and Katmai National Park and Preserve (KATM).

How are we monitoring?

We monitor the nearshore using a site-selection process that allows us to make statistical inference over various spatial scales, from regional to site-specific and to evaluate potential impacts from more localized sources—especially those resulting from human activities, including lingering effects of the oil spill. We look at both static (e.g., substrate, exposure, bathymetry) and dynamic (e.g., variation in oceanographic conditions, productivity, and predation) drivers as mechanisms linked to ecosystem change.

We monitor over 200 species, as well as a number of ecological processes. The methods used vary widely and are described within the summaries for each of the metrics linked to the right.

Macroalgae are primary producers in nearshore ecosystems of the northern Gulf of Alaska. Photo credit: Mandy Lindeberg, NOAA.