News Release published by the National Park Service

News Release Date: April 5, 2021

Contact: Heather Coletti, Heather_Coletti@nps.gov

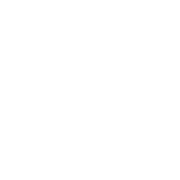

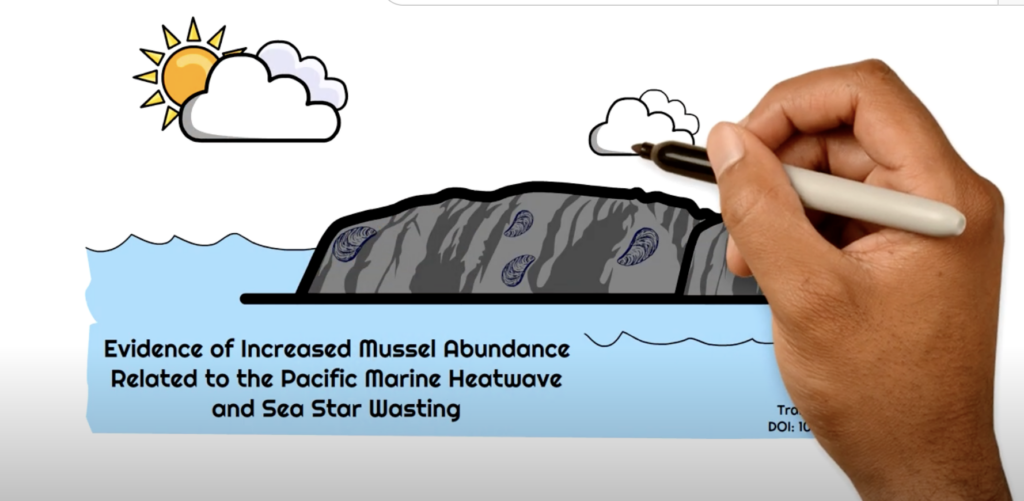

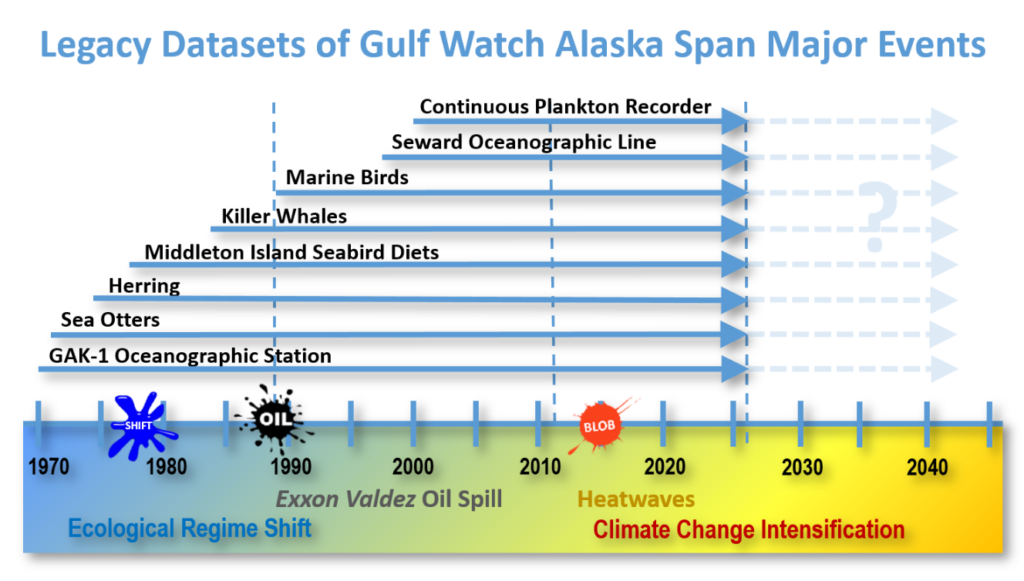

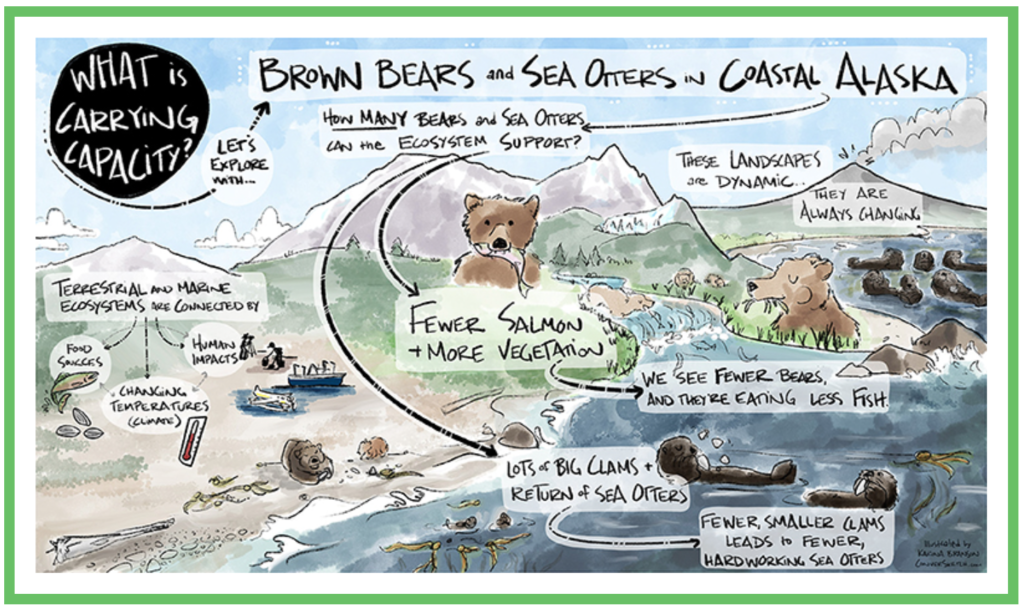

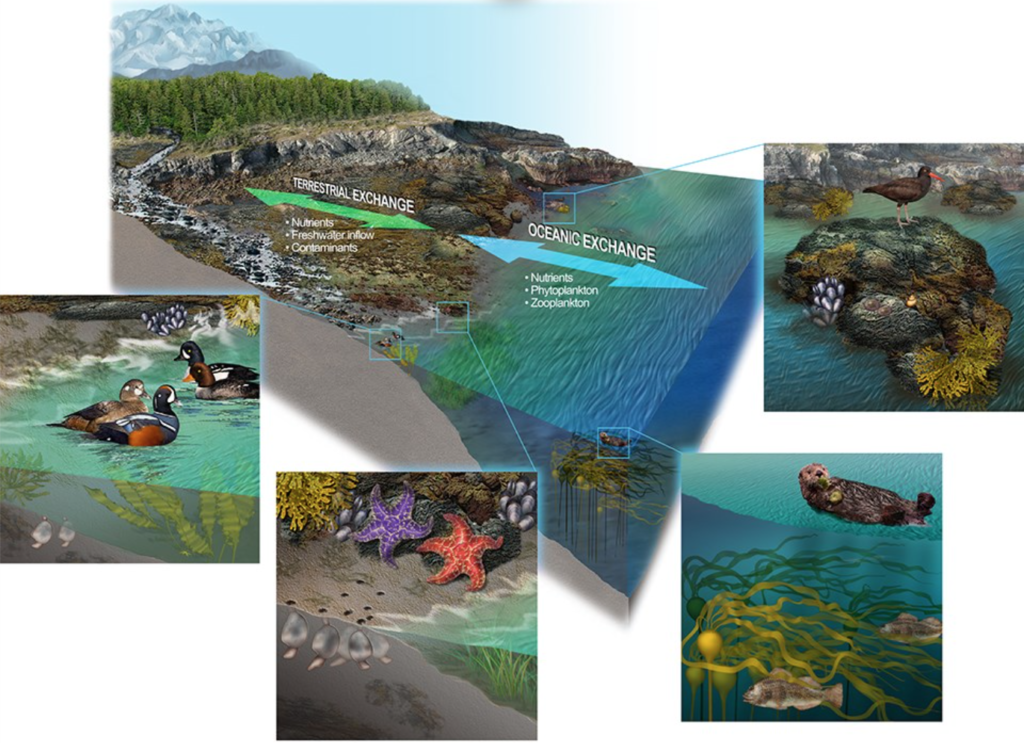

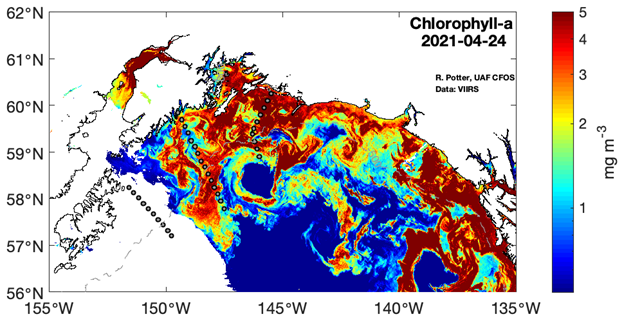

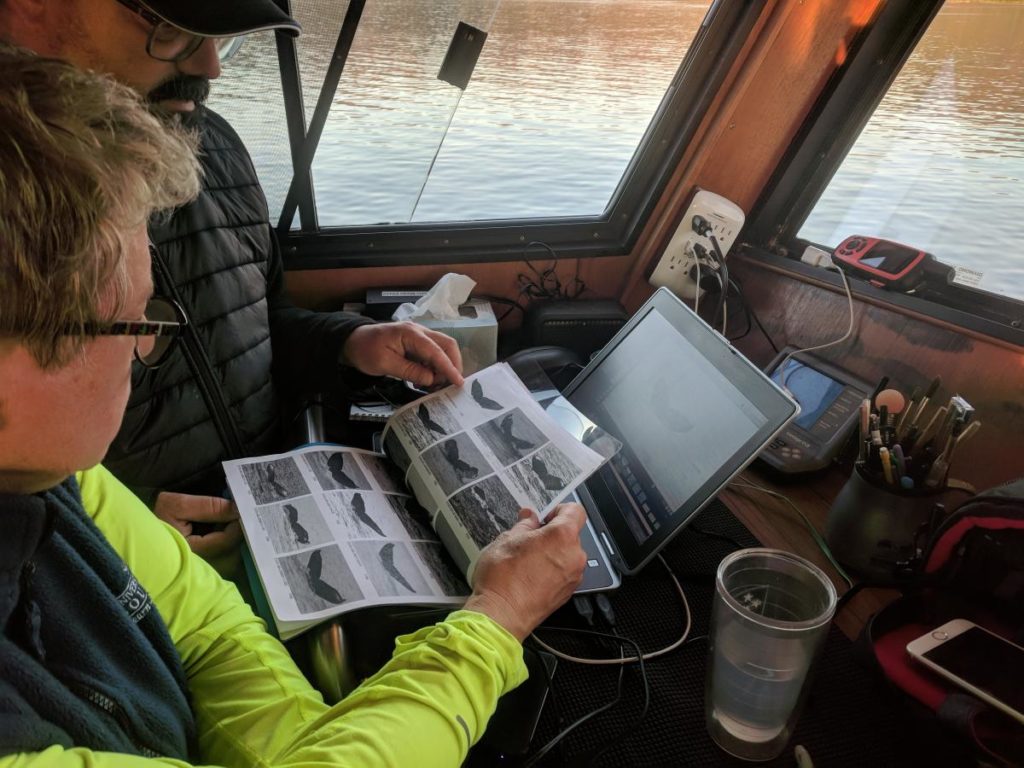

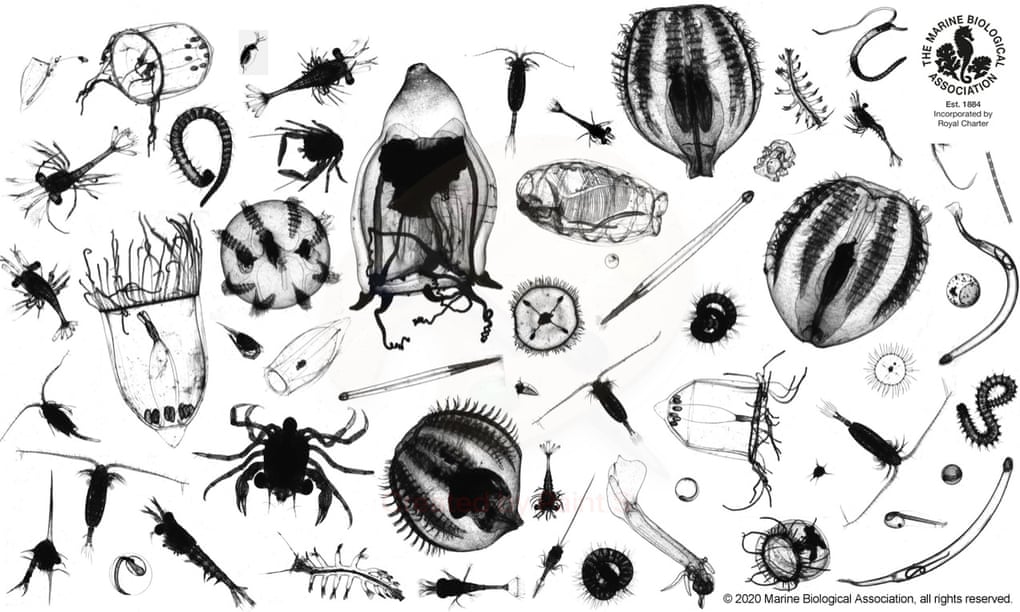

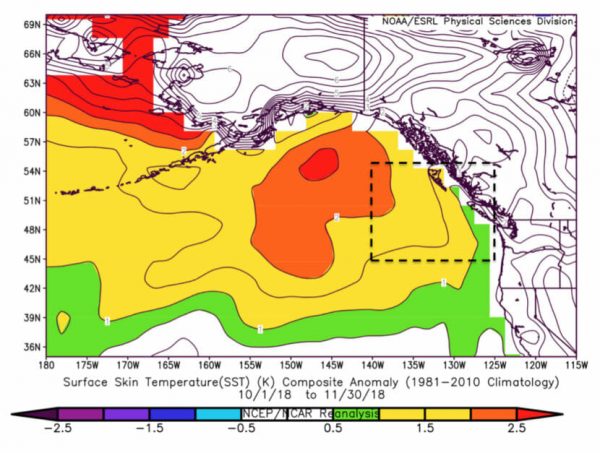

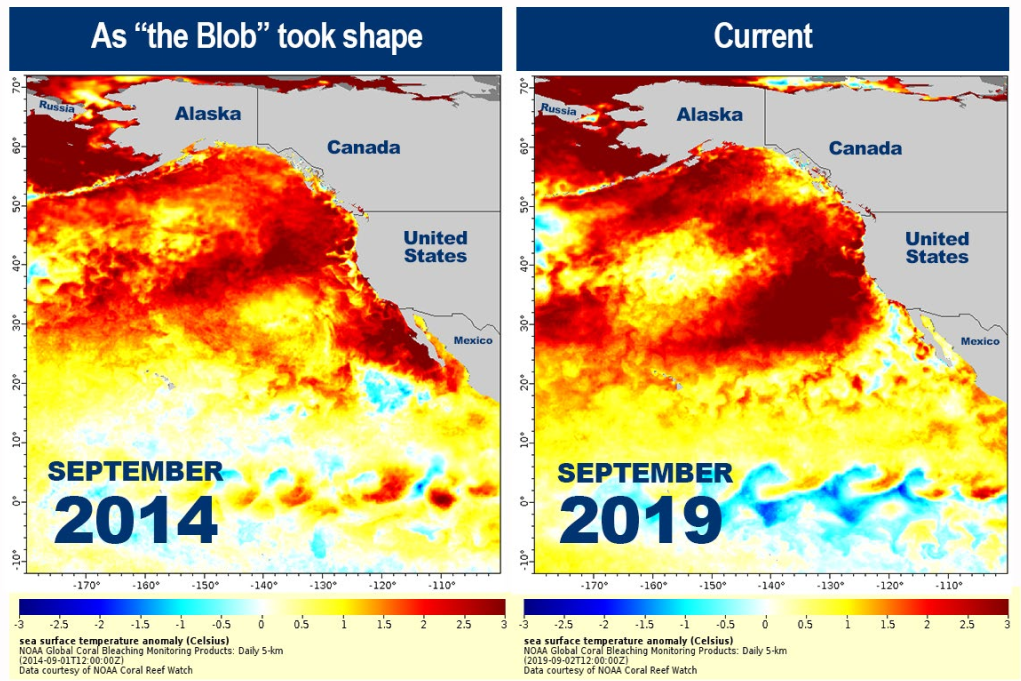

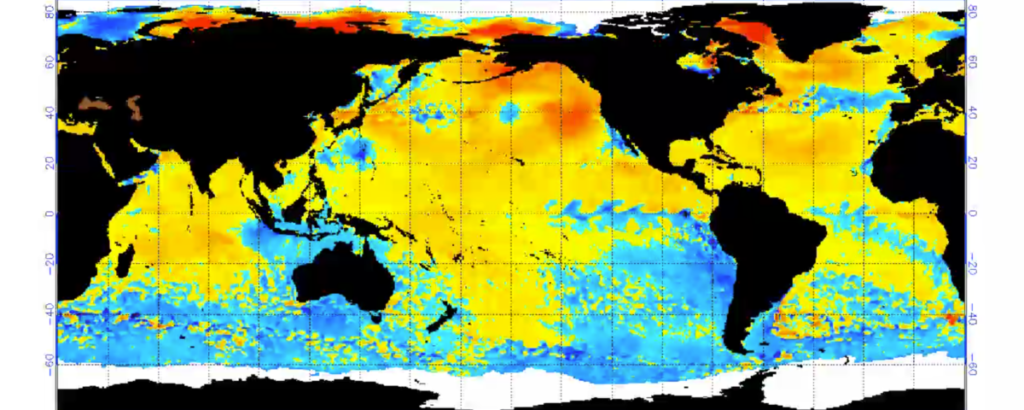

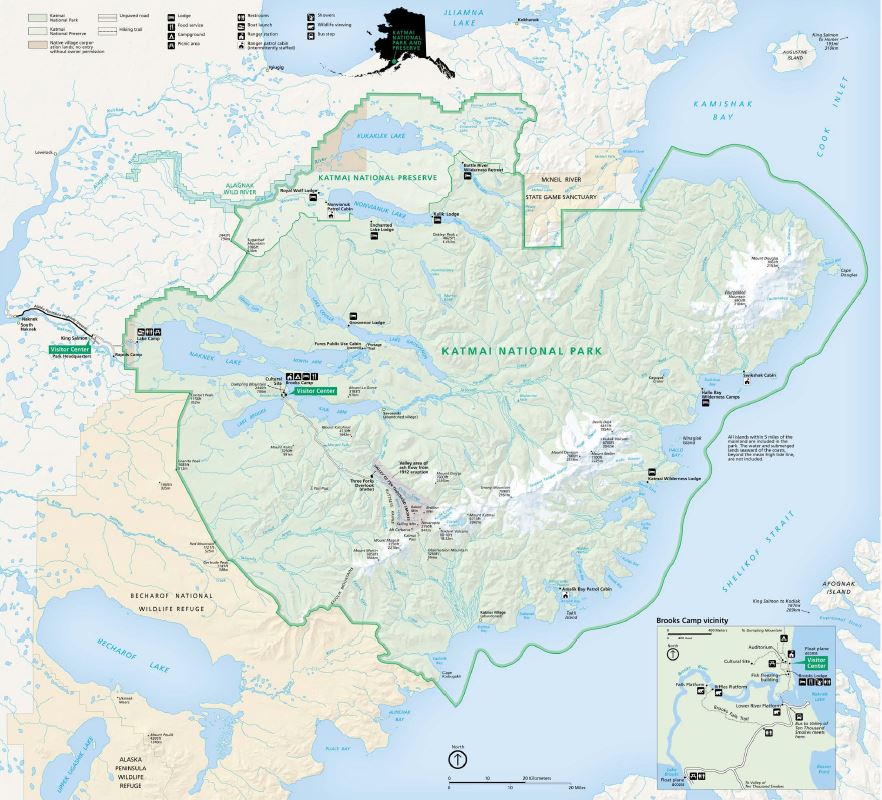

The recent Pacific Marine Heatwave (PMH) was unprecedented in its intensity and duration. Its spatial extent (the large area impacted), magnitude (how unusually warm it was), and duration (how long it lasted) made it the largest heatwave on record. While marine heatwaves have occurred in the past, they have become more prevalent and intense over the last century. The warm waters documented offshore also manifested in the coastal waters of the Gulf of Alaska. Changes from generally colder to warmer water anomalies were coincident with major changes in community structure at our intertidal sites. In the rocky intertidal, the Gulf Watch Alaska Long-term Monitoring Program documented changes in community structure across 21 rocky intertidal sites, covering four regions in the Gulf of Alaska (GOA) in response to the warming. The intertidal zone is a biome considered to be resilient to environmental extremes (heat, desiccation, storm surges, etc.). Intertidal communities are generally structured by local-scale drivers, but the strength and duration of the PMH overwhelmed those local scale influences. The result was the homogenization of these diverse communities across the Gulf through a shift from autotrophic dominated species (macroalgae) to one of heterotrophs (mussels and barnacles). This homogenization of marine communities has been documented elsewhere as a response to prolonged marine heatwaves. The loss of Fucus distichus (rockweed), one of the primary macroalgae in the rocky intertidal in the GOA, also meant the loss of a foundational species that creates habitat for other species. While Fucus was replaced by two other foundational species that also create habitat, mussels and barnacles, the shift in community composition, and hence, ecosystem function, will have to be evaluated over time (Weitzman et al. 2021).

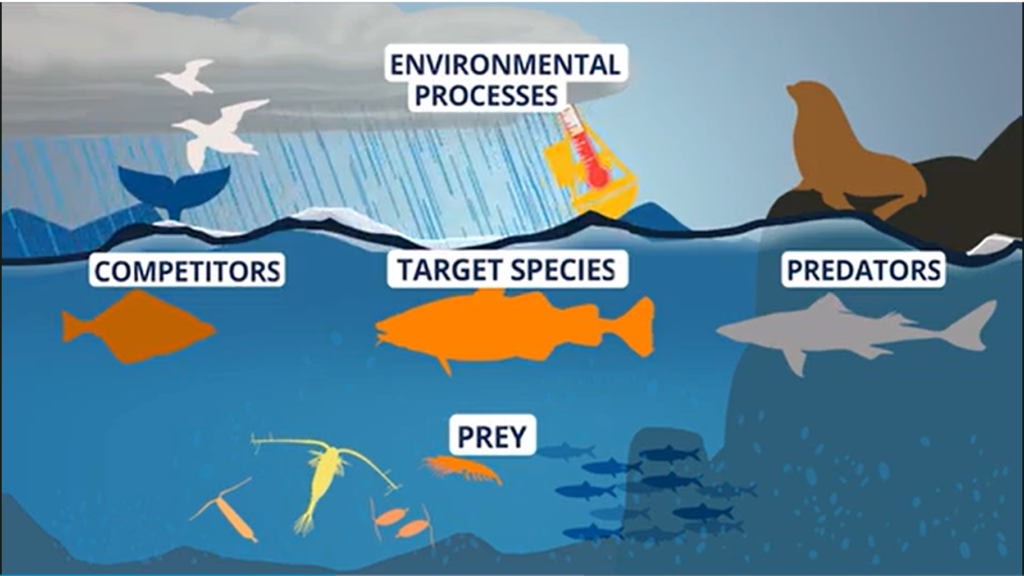

Two other recent papers, also stemming from the collaborative Gulf Watch Alaska Long-term Monitoring Program, documented biological responses in the northern Gulf of Alaska to the recent Pacific Marine Heatwave (PMH). These responses occurred across food webs and biomes, from nearshore to offshore, and, in some cases, have persisted beyond the duration of the PMH in the North Pacific. In many cases, the perturbation was strong enough to override typical drivers of the system and it is uncertain whether the Gulf of Alaska will return to a pre-PMH state (Suryan et al. 2021).

For example, disruptions to the transfer of energy in the pelagic food web were driven by the heat-induced collapse of forage fish populations. Through varying life-histories of these forage fish species, this food web can be resilient to fluctuations in forage fish species’ abundance. However, the synchronous collapse of key forage fish populations, along with shifts in age structure, size, growth, and energy content suggests that the forage community as a whole was unable to mitigate adverse impacts of the heatwave, leading to the starvation of many seabirds, marine mammals, and other fishes (Arimitsu et al. 2021).

In the winter of 2015-2016, researchers and volunteers counted 62,000 bird carcasses washed up on beaches from California to Alaska. Because not all dead birds wash up on the shore, we estimate the total to be as many as a million dead birds. They all starved; no evidence of other causes of mortality was found (Piatt et al. 2020).

To access the recent publications and interact with the How Marine Heatwaves are Changing Ocean Ecosystems story map (developed by NPS), visit: https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1349/marineheatwaveimpacts.htm