Why are we monitoring?

Sea otters are an important component of nearshore ecosystems in the northern Gulf of Alaska. Sea otters have strong effects on prey communities and sea otter numbers and behavior reflect habitat conditions; because of these features, sea otters are particularly useful indicators of ecosystem status. We monitor several aspects of sea otter populations, including diet and energy intake rates based on foraging observations, age-at-death based on examination of carcasses, and distribution and abundance using aerial and skiff surveys. Through foraging observations, we can also use the sea otter to infer how the nearshore subtidal community is changing over time. Taken together, these metrics provide important insights on the status of sea otter populations and the condition of the environments in which they occur.

In addition to their important role within nearshore communities, sea otters are of high conservation interest in their own right, as a highly recognized and societally-valued marine mammal. Also, sea otter populations in the southwest Alaska population segment (which includes coastal habitat of Katmai National Park and Preserve) are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Monitoring sea otter populations, as well as other nearshore ecosystem components related to sea otter population health, will result in important information to better understand population status and trajectories (see Bivalves and Intertidal Communities).

Where are we monitoriing?

We monitor sea otters across a broad swath of the northern Gulf of Alaska within the area affected by the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Study regions include western Prince William Sound (WPWS), Kenai Fjords National Park (KEFJ), Kachemak Bay (KBAY), and Katmai National Park and Preserve (KATM).

How are we monitoring?

There are three different ways sea otter data are collected:

- Aerial surveys are conducted to estimate trend in sea otter density over time and map their distribution. Skiff surveys provide additional data on abundance and reproduction.

- Sea otter foraging data are collected annually to estimate diet composition and energy intake rates (Kcal/min), i.e., the amount of prey energy consumed per unit of time while an otter is foraging. These rates are used to indicate population status relative to a food-limited carrying capacity.

- Carcasses are collected to estimate the age-class distribution of dying otters, which provides insight as to the status of the population.

What are we finding?

Sea Otter Density

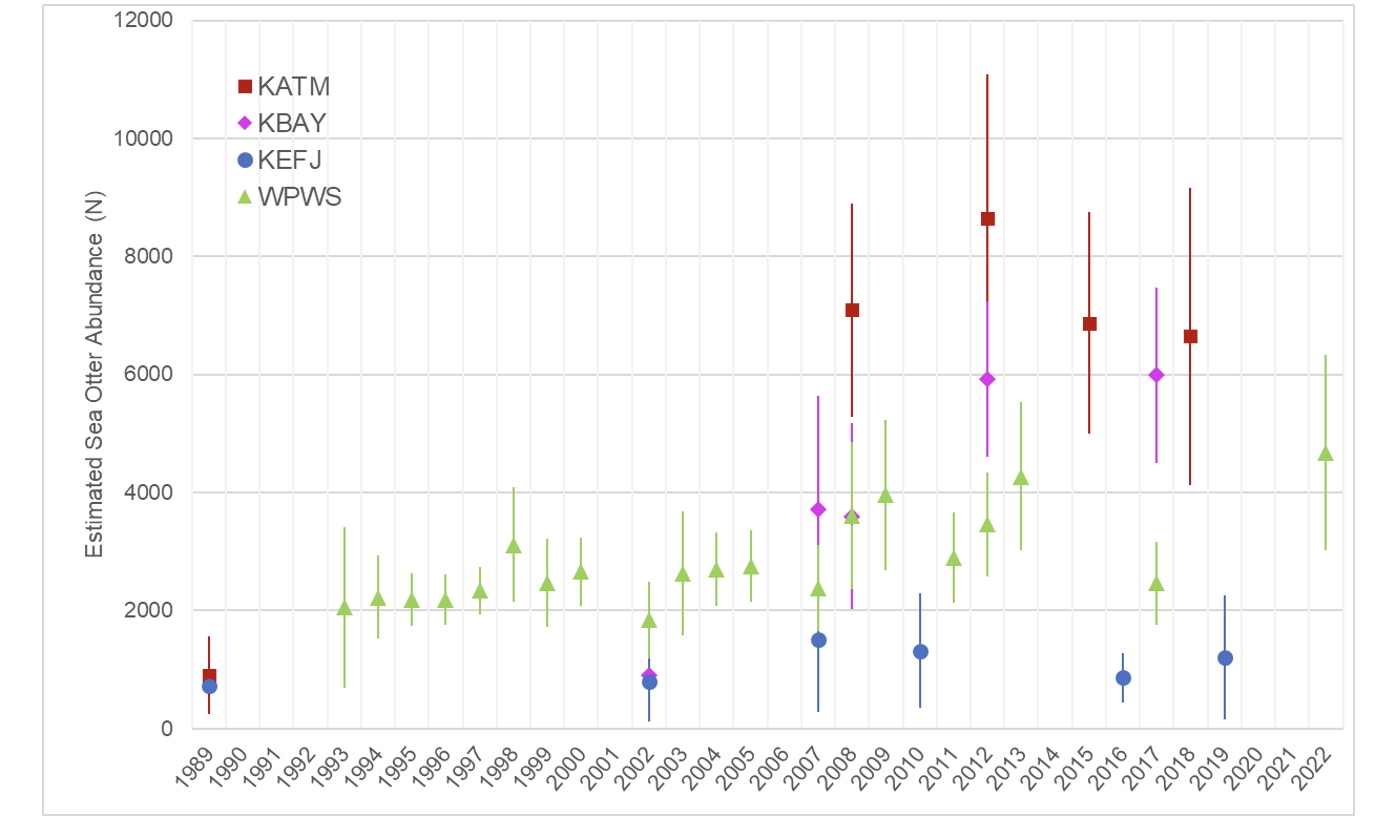

Aerial survey data collected during Gulf Watch Alaska, combined with surveys conducted prior to 2012, paint a picture of very different population status and trajectories among our study regions. KATM and KBAY have had rapidly increasing densities in recent decades, with densities stabilizing at high values relative to KEFJ and WPWS, reflecting differing prey abundance and subsequently differing carrying capacity. KEFJ has had consistent but low densities, reflecting a stable population in an area with lower prey availability. WPWS also has relatively low densities, with an increase around 2008 thought to be related to recovery from the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

Mean estimated sea otter abundance (±95CI) by year for Katmai (KATM red), Kachemak Bay (KBAY purple), Kenai Fjords (KEFJ blue), and Western Prince William Sound (WPWS green).

Sea Otter Diet and Energy Intake

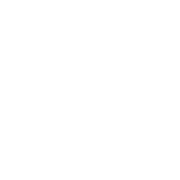

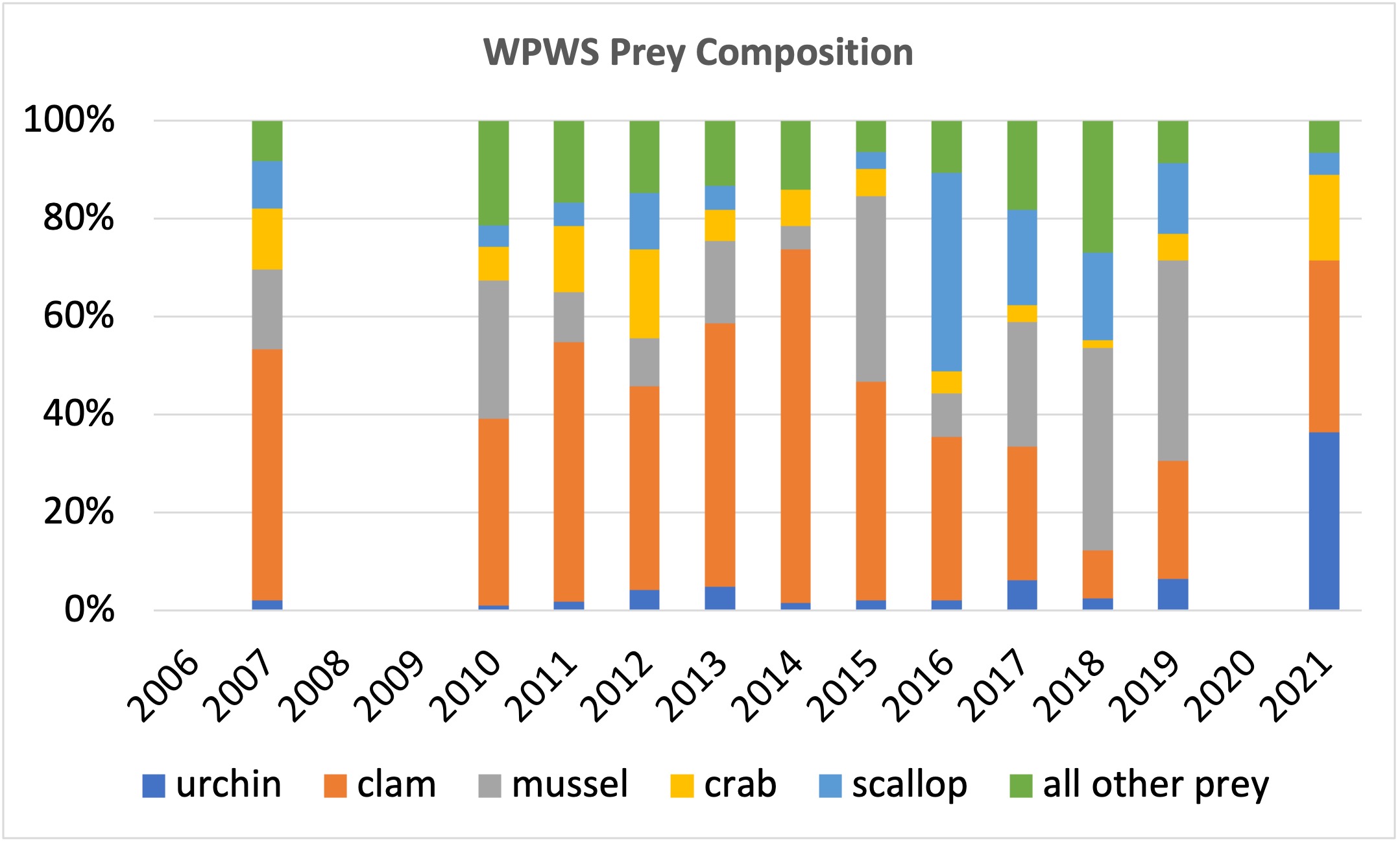

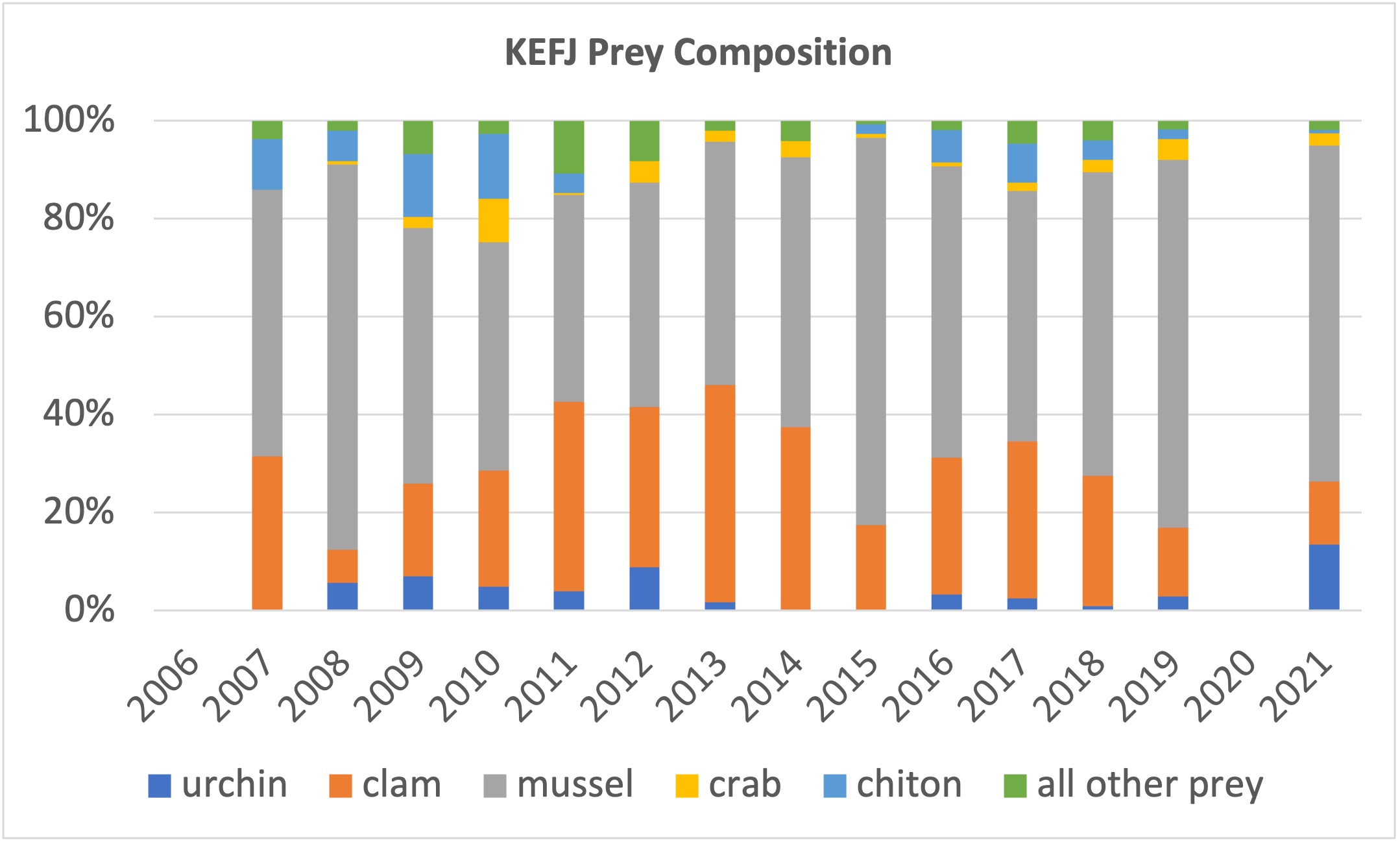

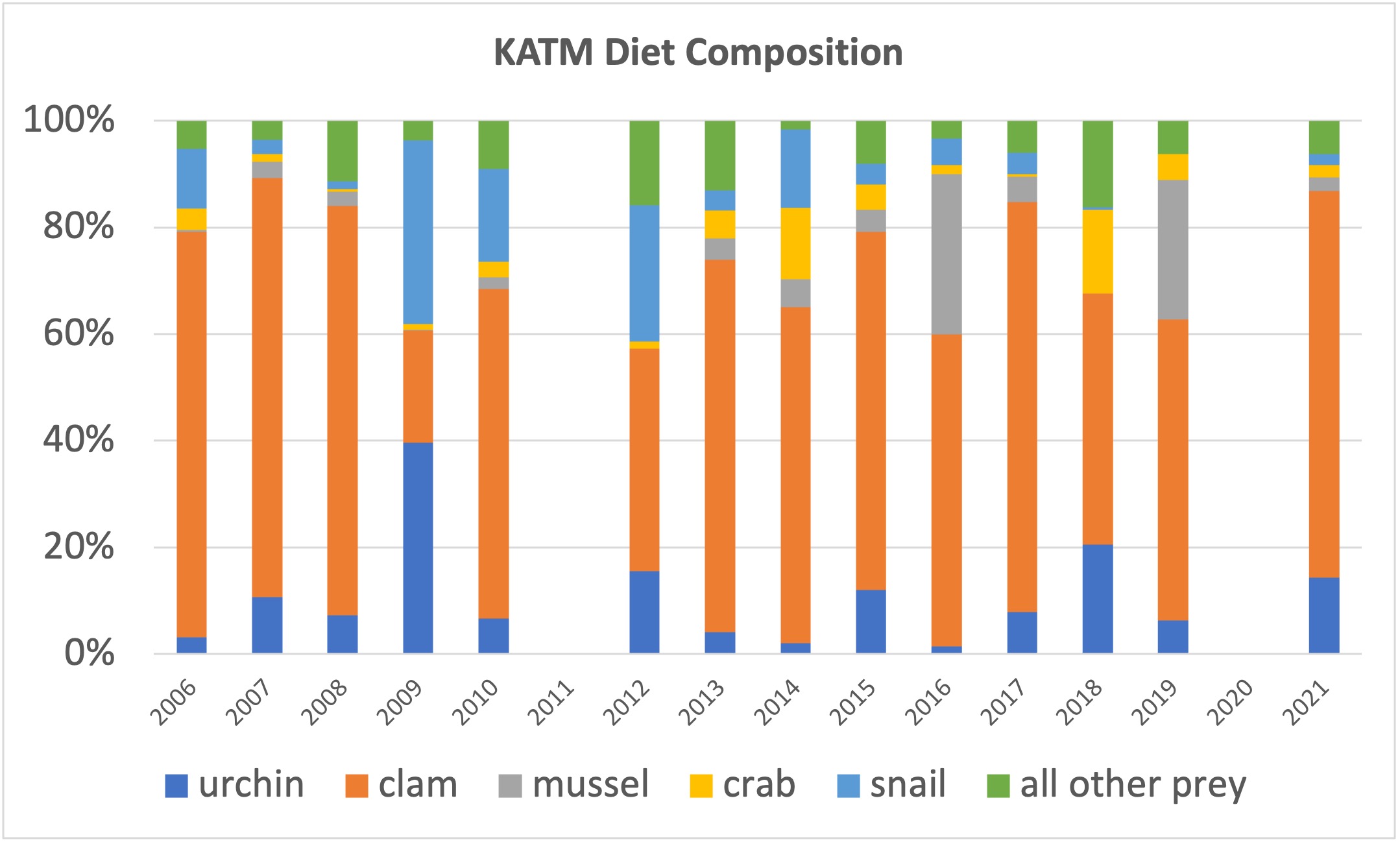

We have found that proportions of prey types in sea otter diets vary by region. The sea otter diet at KEFJ is comprised of about equal proportions of mussels and clams, while in contrast, diet in KATM continues to be dominated by clams with an assortment of other, less-important prey. WPWS sea otters appear to have shifted recently from a diet primarily of clams to one higher in mussels in 2018, consistent with recent increases in large mussel abundance (see Bivalves). In KBAY, where annual foraging observations were initiated in 2018, sea otters are eating a relatively high proportion of mussels. Coinciding with the increase in large (≥20 mm) mussels across all study areas (see Bivalves), we have found increases in mussel consumption by sea otters in recent years.

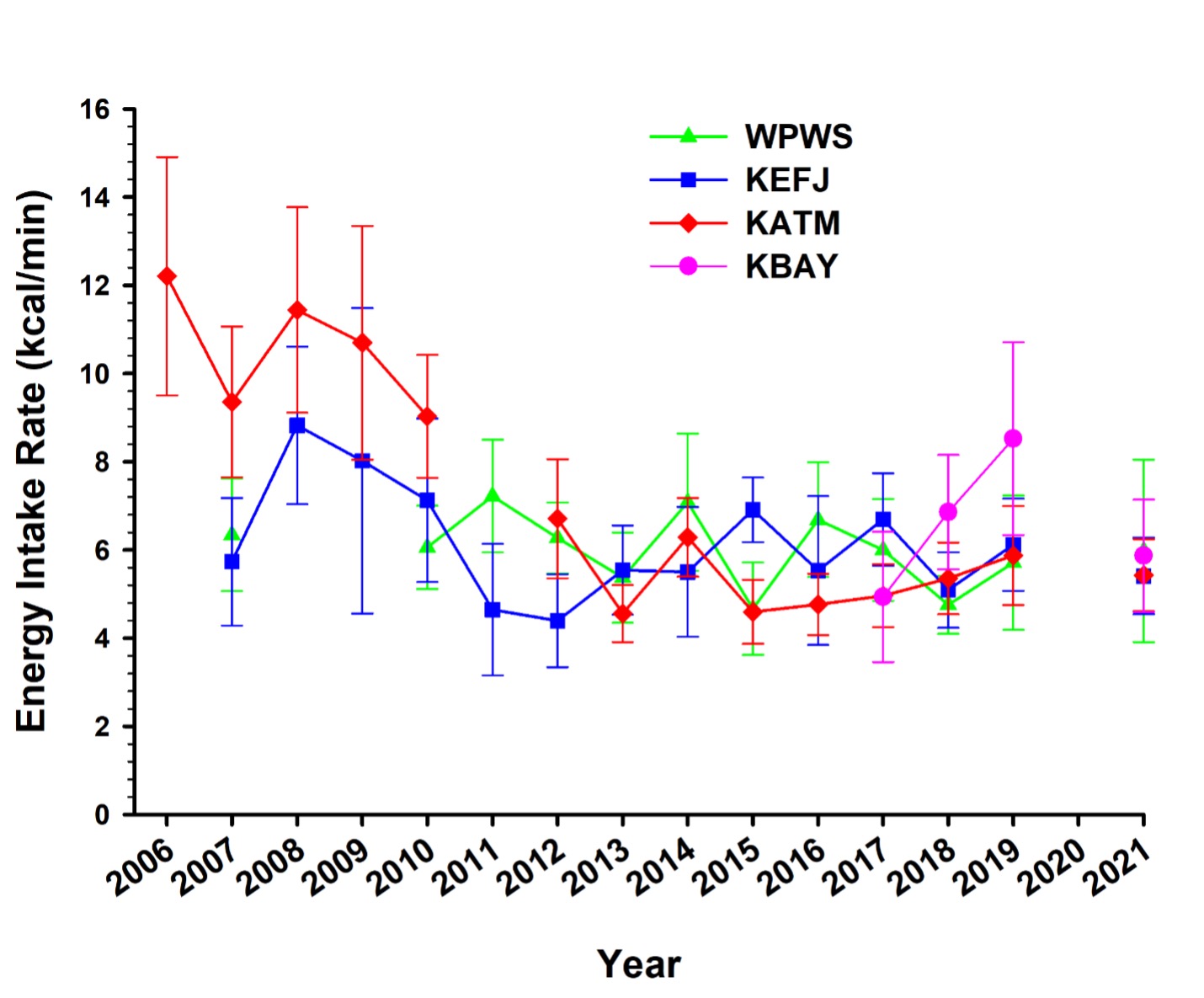

At KATM, foraging sea otter energy recovery declined from ~ 12 Kcal/min in 2006, to about 7 Kcal/min in 2012 (when the population peaked), to about 5 Kcal/min in recent years, reflecting a population that has reached carrying capacity and has remained fairly stable since that time. Average values through 2018 at KEFJ and WPWS are about 6 Kcal/min, also consistent with populations at or near carrying capacity. Energy recovery rates at KEFJ and WPWS are consistent with estimates of population abundance that remain relatively stable over time.

Sea otter energy intake rates across all four Gulf Watch Alaska regions: Katmai National Park and Preserve (KATM), Kachemak Bay (KBAY), Kenai Fjords National Park (KEFJ), and western Prince William Sound (WPWS). Error bars indicate ±1SE.

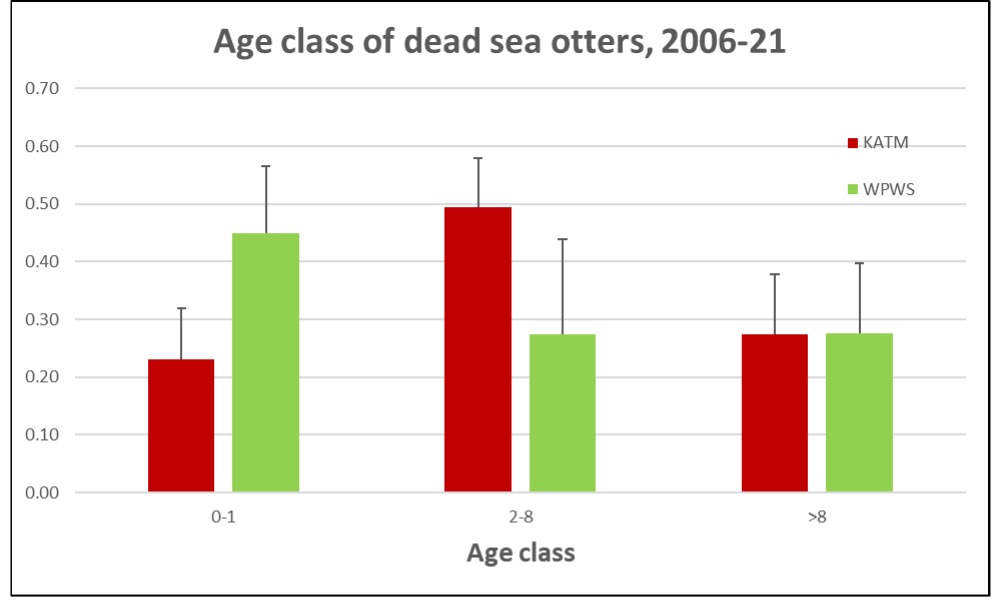

Sea Otter Mortality

Age-at-death data are another useful metric for understanding sea otter population status. Data from KATM did not meet the typical “natural” age-dependent mortality trend. Instead, we found high proportions of mortality among prime-aged animals based on carcass data. With additional research, we found a non-age-specific mortality factor at work, specifically brown bear predation.