Pirouette above the sea,

dive fast on pleated wing

Sand lance for a meal

Why are we sampling?

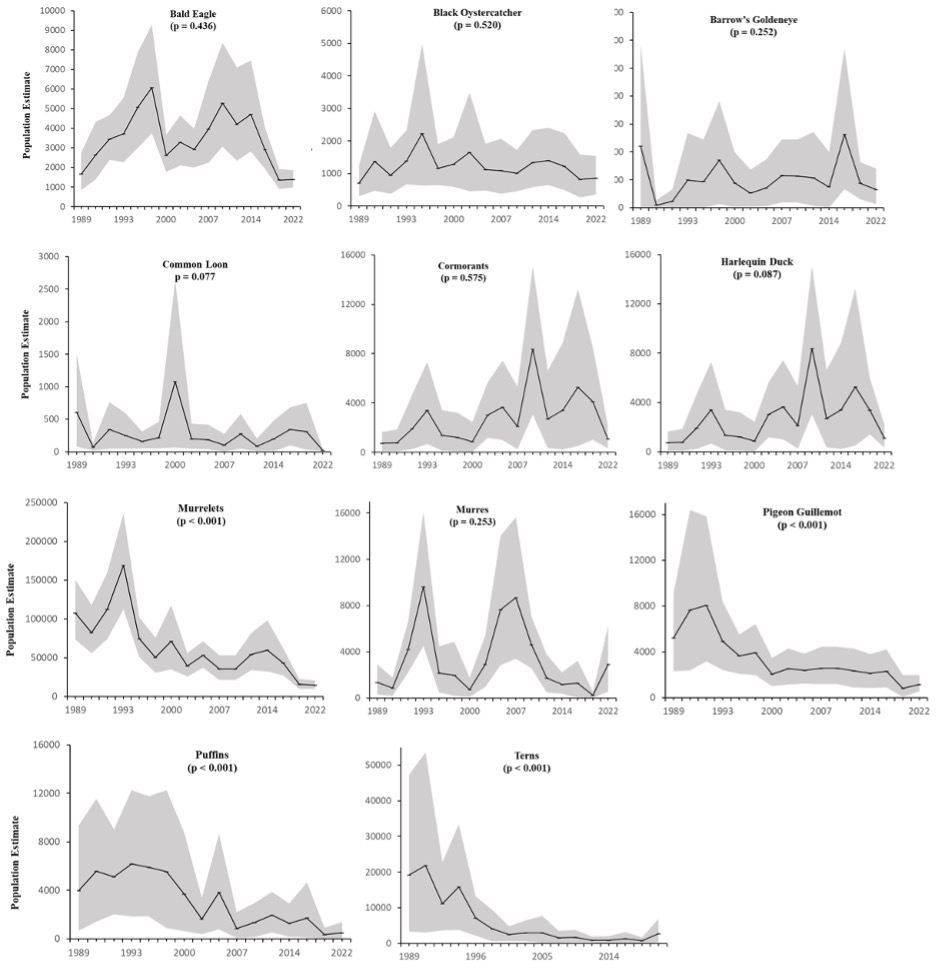

Almost 30,000 dead marine birds were recovered following the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Based on modeling studies using carcass search effort and population data, an estimated 250,000 marine birds were killed in Prince William Sound and the northern Gulf of Alaska. We are continuing to monitor these marine bird monitoring and to synthesize our data with that of other monitoring projects to help determine whether populations injured by the spill are recovering, and if not, why not, and how other environmental variables such as anomalous warm or cold periods affect populations.

Where are we sampling?

We sample throughout all marine waters of Prince William Sound. Using a stratified random sampling design, we sample three strata: shoreline (within 200 m of land), coastal-pelagic (pelagic transects that intersect land), and pelagic (offshore transects). Because 351 transects were randomly chosen, and the same transects were sampled each survey, they represent the variety of coastal and offshore habitats that occur in PWS.

How are we sampling?

We conduct surveys in three strata every other year during the month of July, using three fiberglass boats traveling at low speeds (6-12 mph) to survey the area over a three-week period. Two observers and a boat operator record all marine birds and marine mammals within the transect “window” (100 m either side of the boat). Each team records species, numbers, and behavioral observations directly into a computer, which also records location (latitude and longitude) and environmental conditions. Having exact location information allows us to later overlay our observations and track lines with habitat data such as bathymetry, as well as satellite data on sea surface temperature and salinity.

A PIGEON GUILLEMOT (CEPPHUS COLUMBA) ENJOYS A MEAL OF FORAGE FISH (SANDLANCE OR CAPELIN). PIGEON GUILLEMOT POPULATIONS HAVE STILL NOT YET RECOVERED TO PRE-SPILL LEVELS FOLLOWING THE EXXON VALDEZ OIL SPILL. PHOTO CREDIT: TAMARA ZELLER, USFWS.

What are we finding?

Thirty-three years after EVOS, there is no consistent difference in marine bird abundance between oiled and unoiled areas. In fact, the abundance of several species was declining more rapidly in unoiled versus oiled areas. There is a consistent PWS-wide pattern, however, with all significant trends in abundance being negative and the majority of species with negative abundance trends over time being piscivorous. Environmental anomalies, such as the marine heatwave event during 2014-2016 with record high sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea, may contribute to slow recovery or continued decline in some birds. This warming led to abrupt changes in pelagic food webs and increased exposure of marine organisms to harmful algal blooms and biotoxins. The resulting reduction in prey availability and quality has detrimental implications for marine bird populations. These results suggest a primary driver of PWS marine bird population declines over the past 33 years is reduced availability of prey, particularly forage fishes.